In addition to using commercial hardware, the IMRS plan is based on a number of variations to the DRA intended to decrease cost, improve safety and increase the return on investment and the utility of the base. In this section several of the most important differences from the DRA, and their reasons, are discussed. These form the core design philosophies underlying the overall plan.

4.1. Predeploy the Hab; Land in Capsules

In Mars Direct, the crew travel to Mars, and land in, the habitat. In the DRA, the habitat waits on Mars orbit for arrival of the crew in the MTV, then they transfer to the habitat and use it for Mars descent. In Blue Dragon, however, the SHAB, like the MAV, is predeployed to Mars in advance of the crew, and activated and checked out remotely. Instead of landing the crew on Mars in a habitat, a Red Dragon capsule in crew configuration is used. There are several important reasons for this strategy.

Peace of mind

One of the innovations in Mars Direct is that the ERV (Earth Return Vehicle) is landed on Mars one launch opportunity (~26 months) prior to arrival of the crew. Once at Mars, the ERV’s power system and propellant plant are activated and the methalox bipropellant is manufactured quickly to minimise hydrogen boil-off. In this way, mission planners know that there’s an ascent vehicle on Mars, full of propellant and ready to go, before the crew even leave Earth. This idea greatly improves safety and was incorporated into the DRA; it is also included in Blue Dragon.

If predeployment is a good idea for the MAV then it applies equally well to the SHAB. The SHAB’s systems can be tested and validated, including ISRU, power and communications, before the crew leave Earth. Knowing that the SHAB has safely landed and is fully operational will significantly improve confidence of mission planners and crew.

ISRU

Predeploying the SHAB creates a window of time during which breathable air and potable water for life support can be manufactured from local Martian resources. Taking this approach obviates the need to bring some or all of these resources from Earth, thus reducing mass and cost. Importantly, as mentioned below, this can be done without risk to the crew.

Safety

The SHAB will be heavier than anything else ever landed on Mars before, and because Earth’s atmosphere and gravity are completely different to Mars’s, it will not be possible to run a high-fidelity end-to-end test of SHAB EDL prior to its actual deployment. With the advanced computer modelling capability now available, a Mars landing can be simulated much more accurately than any aspects of space missions to date. Nonetheless, computer simulations are never 100% perfect. Some aspects of the SHAB’s EDL system can be tested on Earth; for example, aerodynamic and aerothermal loads could be tested in Earth’s upper atmosphere above 30 km altitude to simulate the thin Martian air. Terminal landing systems can be tested using a 0.38 mass scale model. However, although a high confidence in a successful landing of the SHAB can be achieved, the EDL system for delivering such a large and heavy item to the surface of Mars will not be properly tested until the actual Mars landing.

It will therefore be much safer to land the crew in a 6 tonne capsule rather than in a 20-30 tonne habitat or descent vehicle. This is especially true if the use of capsules for EDL has already been tested and proven to work several times. Before the first human mission, Dragon capsules will probably have been used many times for carrying crew and cargo between Earth orbit and surface, and possibly also several times for delivering experiments and cargo to Mars.

If the SHAB crashes on Mars there’s no risk of LOC (Loss Of Crew), because they won’t be in it. In that event, the design of the SHAB or its EDL system can simply be improved, and another built and sent, and this process can be repeated until success is achieved. A crew will only be sent to Mars once there’s a fully operational MAV, SHAB, CAMPER, power system and everything else necessary for a successful surface mission already in place.

Cost

With a base-first strategy, if the architecture does not require landing in a habitat then each mission does not require another one; only another capsule. Since capsules will be significantly cheaper, this greatly reduces the cost of each mission.

4.1.1. Getting to the SHAB

Because the crew do not land in a habitat, a method for safely reaching the SHAB on arrival is necessary.

The capsule will not be able to land too close to the SHAB, or any other part of the base, because dust and debris thrown up by the engines during the landing may cause damage to the SHAB or cover the solar panels with dirt. The capsule LZ will therefore need to be at least a few hundred metres away from the SHAB, or at least downhill from it.

However, after spending 6 months in microgravity, it would be impractical to expect the crew to walk that far in marssuits immediately after landing on Mars, as they may have become weakened to some degree.

The solution is to pick the crew up in the CAMPER. After the dust has settled post-landing, the CAMPER will be driven from the SHAB to Einstein’s LZ under remote control by the crew. As a backup, MCC (Mission Control Centre) will also be able to remotely operate the CAMPER.

The path the CAMPER will take between SHAB and the LZ will have been driven along several times before they arrive. The LZ will be selected in advanced by exploring the surrounding terrain, both from orbit and by exploring the area with the CAMPER via remote control, and identifying a smooth and flat location with a clear path to the SHAB. Using the CAMPER’s excavator attachment and/or robotic arms, the path can be made smoother, clearer and safer during the available time, thus improving the probability that the crew will reach the SHAB safely. This strategy relies on the ability to land Einstein with a high degree of precision.

The crew will be wearing MCP (Mechanical Counter-Pressure) marssuits during EDL, and will enter and exit the CAMPER and the SHAB through their respective airlocks.

If the CAMPER is unable to reach Einstein for some reason, then the backup plan will indeed be for the crew to walk. Although they may have become weakened during the outbound trip, if they have been diligent with their exercise and nutrition, as they should, then a short walk in the light Martian gravity should be achievable.

4.2. Multiple Missions

The DRA specifies a program of three missions for these reasons:

- A more substantial overall return on the necessary investment in hardware development, human resources and intellectual capital can be achieved if the architecture is implemented a minimum of three times.

- To complete the DRA three times will require a total of approximately one decade. During this period new technology will become available, the space industry will have evolved, and it will probably be appropriate timing to develop a more efficient or practical architecture.

This reasoning applies equally well to IMRS, and hence at least three missions should be planned. However, the intention is that this be the minimum number, and that at least 10 missions to the IMRS be conducted in order to establish some basic infrastructure, obtain scientific results, produce new inventions, and plant the seeds of settlement.

The goal is to establish a permanent human presence on Mars, a base for further exploration, and some fundamental infrastructure elements. Over the coming decades, as the technology develops, HMMs will become increasingly affordable and thus easier for both government space agencies and private enterprise to conduct.

After each run-through of the architecture, opportunities to make improvements will present themselves and each mission will be progressively more efficient, faster, cheaper, safer, or otherwise an incremental improvement on the previous. The first mission will be the most expensive, after which the cost of each mission will decrease as the architecture, designs and hardware components are re-used and improved. Alternately, the same budget can be used to achieve more.

Re-use of the architecture multiple times produces an even greater value benefit in the IMRS than it does in DRA, because the missions are all targeted at the same location, therefore, much of the hardware delivered in the initial predeployment can be re-used by each successive mission. If an ongoing financial commitment can be secured from each participating space agency, this will enable the subsequent development of an updated architecture based on new technology and scientific information, and further exploration and development of Mars can continue.

4.3. Base-First Strategy

Once the IMRS has been built, numerous missions can be conducted to the same location at comparatively low cost. By locating the IMRS in an interesting area and including a long-range surface vehicle such as the CAMPER, crews will still be able to access a sufficiently large area of Mars and perform considerable research.

To highlight the advantage of the base-first strategy (as well as landing crews in capsules rather than in habitats), consider how much analogue research would cost if a new habitat had to be constructed and delivered to a different site for every single mission.

The DRA is designed as a precursor to settlement only in the sense that it would provide data and knowledge useful to future settlement plans; however, any material assets delivered to Mars would not be designed for use by settlers. In IMRS, however, the assets delivered to Mars during the missions form the seeds of a settlement. Components are intended and designed to last as long as possible, and be re-used across multiple missions.

This strategy enables infrastructure to be accumulated at the base, from which each successive mission will benefit. A communications, observation and navigation satellite will be positioned above the base in an areosynchronous orbit. Roads will be built. Transponders will be installed around the base to provide an accurate LPS (Local Positioning System) for use by vehicles and robots. Habitats, greenhouses, surface vehicles, power plants and other base components may be re-used, improved, developed, expanded, and integrated with each other and the surrounding landscape until the base can be permanently inhabited. Additional structures may be built from locally-sourced stone and metals, or by tunnelling underground or into hillsides.

A build-up of power-production resources in one location is of particular importance, and demonstrates the real advantage of this approach. Instead of sending shipments of power-production hardware to different locations on the planet, money can be saved by sending multiple shipments to the same location and thereby establishing a reliable and abundant power source at that location. The result is significantly improved energy security and reduced cost, which is crucial for long-term survival on Mars, and the same rationale applies to water, food, air, propellant, surface mobility, manufacturing, and so on.

By sending missions to distinct locations on Mars, it’s true that more could be learned about Mars in the short-term. However, each mission would be almost equally risky and costly, and ongoing missions would be less likely. Sending hardware to a single location means that redundant backups of mission-critical components can be emplaced, thus reducing risk and cost with each successive mission. A permanent human presence on Mars can be established much quicker, and missions can be conducted from the settlement to other locations on Mars. The long-term result will be that more of Mars is explored and a new world will be opened up for human habitation.

The base-first approach obviously represents a huge cost saving; not only the cost of the hardware, but the considerably greater cost of sending it. Once the SHAB and CAMPER are at the IMRS it will only be necessary to deliver another MAV, crew and supplies in order to run each successive mission. If financial resources are available on subsequent missions, it will be possible to send backup components, or valuable additions to the base such as a greenhouse, additional power production or ISRU hardware, equipment for excavation or experiments, or other useful items of hardware that will facilitate settlement.

Focusing on a single location makes it crucial that an especially good one be selected, as will be discussed (see Site Selection).

4.4. Manufacturing and Materials

Amazing breakthroughs are currently occurring in materials and manufacturing that promise to be tremendously beneficial to space exploration.

For example, the combustion chambers of the SuperDraco thrusters in SpaceX’s Dragon V2 capsule are the first ever 3D printed rocket engine components, printed using direct metal laser sintering of a material called Inconel, which is an alloy of iron and nickel. The benefit of manufacturing parts this way is reduced mass, improved performance, and faster, cheaper production.

A related technological breakthrough is the development of nanostructured materials. Rather than being completely solid, these materials are comprised of tiny trusses at the nanoscale. The resulting materials can be stronger then steel, yet weigh significantly less; potentially even orders of magnitude less.

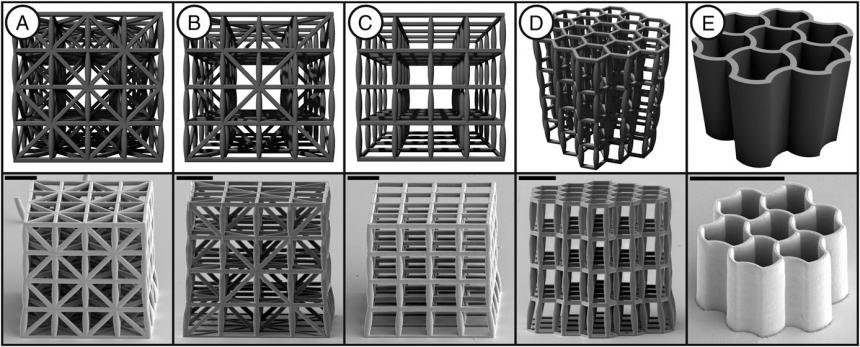

Some examples of truss forms printed in alumina are shown below:

These micro trusses were 3D printed by German scientists using 3D laser lithography to create materials with strength comparable to steel, yet with one tenth the density (Bauer et al. 2014).

Nanostructured materials could become critical features of space missions, significantly reducing the mass of spacecraft components and thereby greatly increasing the utility of launch vehicles. In addition to mass reduction, this form of manufacturing can confer additional mechanical properties on components. Propellant tanks, for example, can not only be made much lighter, but also less permeable, and with enhanced resistance to microcracks.

One tenth the vehicle mass means one tenth the propellant requirement. Less propellant also means less tankage, further reducing the overall mass. If the vehicle can be made significantly lighter, then smaller or fewer rocket engines are necessary to propel it. Thus, even a modest reduction in spacecraft mass can ultimately translate to a significant reduction in IMLEO (Initial Mass in Low Earth Orbit), with a corresponding reduction in cost. Reduced vehicle mass can also translate to increased payload mass.

3D printing and nanostructured materials are receiving considerable attention and will improve dramatically in the coming years. Although the policy for development of the IMRS plan has generally been to base it, as much as possible, on present-day and near-term technologies with high TRL, these technologies are evolving so rapidly, and promise such enormous benefits, that a degree of reliance on their availability has been accepted.

Through 3D printing, robust and high-performing engine parts can be created at a fraction of the cost and time of traditional manufacturing methods. - Elon Musk